The beautiful islands that could help stop killer diseases

In an article on BBC news LSHTM's Prof James Logan outlines how an innovative research collaboration in Guinea-Bissau to evaluate novel strategies for disease elimination may help inform public health programmes worldwide.

Travellers to the remote African islands of Bijagos can expect to find a tropical paradise of pristine beaches and lush rainforest.

But the islands are not just beautiful. They are also a natural laboratory, providing a unique setting in which to study cures for some of the world's deadliest diseases.

A collection of 18 islands and 70 islets off the coast of Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, the Bijagos are home to about 30,000 people with their own language and unique traditions.

They also teem with wildlife, including the rare saltwater hippopotamus and giant sea turtle, which thrive in this remote spot.

But these tranquil islands are home to many serious illnesses and conditions. Life expectancy on Guinea-Bissau is about 60, and on the Bijagos Islands it is thought to be much lower.

Malaria, a severe eye infection called trachoma, lymphatic filariasis - a chronic swelling sometimes known as elephantiasis - and intestinal worms are particular problems.

However, the islands may also hold the secret to tackling the very diseases that blight them.

A natural laboratory

Medical researchers have been working on the Bijagos Islands for several years to see if they can get rid of certain diseases from certain islands.

The reason that the islands work so well as a natural laboratory is their remoteness.

While this makes some everyday activities difficult, it is a helpful feature when trying to eradicate disease.

The islands' separation by water creates a natural barrier. This allows us to compare different disease control methods, without the risk of cross-contamination between the test sites.

On the mainland, people can readily move in and out of trial areas, contaminating the sites and making it difficult to establish cause and effect.

An island set-up allows us to carefully and accurately measure the impact of any intervention made.

While there are many archipelagos around the world, few have islands close enough together to allow us to work there, but far enough apart to minimise interference during experiments.

There are also few islands with this layout that are home to so many diseases.

Researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) initially focused on trachoma, an infectious disease that turns the eyelashes inwards. Affecting 1.9 million people globally, it is the world's leading cause of preventable blindness.

Trachoma can be transmitted if contaminated hands, clothing or infected flies come into contact with the eyes. It is caused by a form of chlamydia bacterium and often spreads in crowded areas with inadequate sanitation.

The disease is found in 42 countries around the world, and at one point, there were some villages on the islands where every single child had the disease.

Dr Anna Last from LSHTM identified high risk areas for trachoma, before treating entire communities with antibiotics to end the cycle of transmission.

Inner eyelid swabs, taken before and after the treatment, helped the researchers to detect the disease at an early stage. They are also being used to identify which genetic types of infection were present.

This might improve understanding of what happens after local elimination.

If the trachoma returns, we may be able to determine from its genetic strain whether it came from an outside source or re-emerged from within that community.

The results were striking. When she first began her work, 25% of people on the islands had the disease. Now, only 0.3% of people have it.

Not only is this below the WHO threshold for elimination, meaning the disease is all but eradicated from the islands, but the techniques developed could now benefit the wider world.

Malaria

Trachoma is not the only problem facing the people of the Bijagos and several other diseases on the islands are now being tackled.

Our current focus is malaria. This disease is spread when female mosquitoes infected with a parasite bite a human, leading to initial symptoms such as fever and a headache before quickly becoming more severe. Malaria kills almost half a million people worldwide each year.

Given the prevalence of malaria on the islands - with up to one in four people infected - it is unsurprising we found mosquitoes that are very good at transmitting the disease.

Worryingly, we also found that some were resistant to insecticides.

This means the most common ways to control malaria - bed nets and spraying houses with insecticides - may not work, meaning an alternative strategy is needed.

A new drug is about to be trialled, which is transferred to the mosquito via the victim's bloodstream when it bites.

Past treatments have tended to target the malaria parasite within the human body. But this drug targets both the mosquito and the malaria parasite, shortening their lifespan.

In this trial, all the islands will be given the standard control tools, such as bed nets. Some, the "intervention" islands, will also be given the drug. Others, the "control" islands, will not.

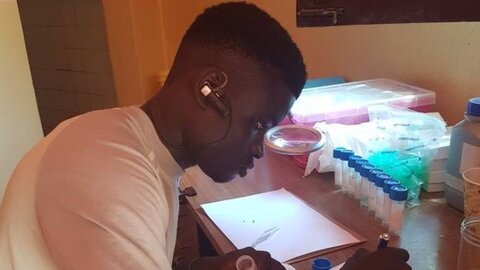

A team of local islanders have been trained in medical skills, such as taking blood samples and screening them for malaria.

They have also learned how to collect and identify mosquitoes, with the help of Ba, one of our field team hoping to become the first entomologist, or insect specialist, on the islands.

Looking to the future

Whether this drug will get rid of malaria on the islands once and for all remains to be seen.

Either way, the lessons learnt from our studies are likely to have an impact far beyond the remote Bijagos Islands.

Every study helps us to learn about the disease itself and how it is transmitted, which shapes future research.

On the islands, this can be done more quickly, with greater control and accuracy. We can see what the effects are in a defined area, reaching an entire population.

The LSHTM project will continue on the Bijagos for at least another five years, and in the meantime, its findings are likely to be used to tackle major diseases like malaria elsewhere.

Access the original BBC article

Research Resources

- Research Project - Studies towards infectious disease elimination on the Bijagos Archipelago of Guinea Bissau

- Research publication - Risk Factors for Active Trachoma and Ocular Chlamydia trachomatis Infection in Treatment-Naïve Trachoma-Hyperendemic Communities of the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea Bissau

- Research publication - Spatial clustering of high load ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in trachoma: A cross-sectional population-based study

- Research publication - The impact of a single round of community mass treatment with azithromycin on disease severity and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis load in treatment-naïve trachoma-endemic island communities in West Africa

- Research publication - Population-based analysis of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis in trachoma-endemic West African communities identifies genomic markers of disease severity